Ryukyu Bingata is a type of dyed textile that has been handed down for generations in Okinawa. Designs inspired by plants, landscapes and natural phenomena of the tropical land, as well as auspicious patterns that originate in China and Japan colorfully decorate the cloth. The repeated motifs give the impression as if the images are fluctuating: as if the painted flowers and butterflies are swaying in the wind, starting to move beyond their contour lines. It almost feels as if we are a part of the landscape.

Ryukyu Bingata is a type of dyed textile that has been handed down for generations in Okinawa. Designs inspired by plants, landscapes and natural phenomena of the tropical land, as well as auspicious patterns that originate in China and Japan colorfully decorate the cloth. The repeated motifs give the impression as if the images are fluctuating: as if the painted flowers and butterflies are swaying in the wind, starting to move beyond their contour lines. It almost feels as if we are a part of the landscape.

Bingata dyeing is believed to originate in the 14th century, during the Ryukyu Kingdom period. It was produced as the clothing for the royalty and upper class, and as the trading goods. Records suggest that there were many bingata dyer shops and pattern makers that worked to the orders from the Royal Household around the Shuri-jo Castle.

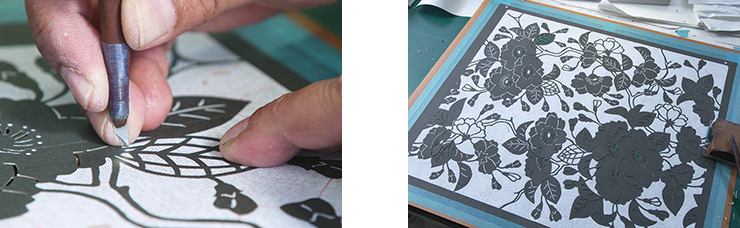

The process of the bingata dyeing involves tingeing the patterns with pigment using stencils and other tools before dyeing the entire textile. A long roll of textile is stretched across, on which many dyers work concurrently to paint patterns in. Especially, the kind dyed with indigo is known as “Eh-gata (indigo pattern)” and is dyed with Ryukyu Indigo. The plant of Ryukyu Indigo is also what has been inherited since the time of the Ryukyu Kingdom period, and its gentle color with a faint flagrance is an essential character of all dyed textiles made in Okinawa. Though the number of producers is decreasing, the indigo plants are still grown in the northern part of Okinawa such as the Izumi area, in the intermountain basin where plenty of water resource necessary for the plant is available. Not only the indigo, but also other plants such as Common garcinia or basho played important roles in the establishing the beauty of Okinawa textiles, as dyes and materials, and often as design motifs.

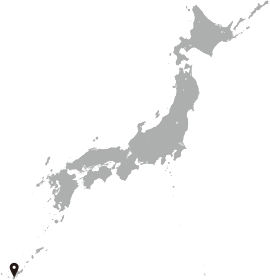

Bold designs of bingata are cut into stencils from drawings. During the Kingdom period, there were painters who specialized in making those drawings. Everything started from rough drawings and sketches. It seems that paintings and craftworks imported from China and design pattern collections purchased from Japan were also sources of designs. Many of the classic patterns still used today were created during this period.

Plants and landscapes of the tropical island have been the most popular motifs in the design. Regardless of the periods in the history, the abundant nature of Okinawa always attracted carvers and dyers and invited them out to make sketches. In the forest of the Yanbaru area, or near the Todoroki Waterfall, flowers of Iju (Chinese guger tree), Deigo (Indian coral tree) or Hibiscus will be swaying in the wind, waiting for them. When the white light of early morning starts to shine, they would witness the once-in-fifty-year moment of the agave flower's blooming on the castle wall. In the midnight sugarcane field, they would encounter birds singing under the moonlight. Artists assimilated themselves to the forest of Yanbaru and become part of it, so that they could closely inspect the micro-cosmos of plants, and gaze deeper into the forest itself. Sketches that they make in such way could capture the few seconds when the ray of light hits a flower petal at sunset or the brief moment before plovers’ footprints on the beach get washed away by waves, and allowed them to create bingata out of them.

“If it was there today, it will be there tomorrow, too.”

Each of these scenes had been captured because an artist was there at the right location at the right time. It is as if those landscapes were given to us from Okinawa as gifts. Some of them may have been lost forever. There may be even landscapes of the future no one has yet to see. Among the layers of landscapes accumulated like strata, vestiges of the erstwhile kingdom may be found. All possible landscapes are captured in bingata designs as a form of eternity.

Under the strong sunshine of Okinawa, flowers, grass and trees, the ocean and everything on the island seem to be shining with vivid colors. Scientifically speaking, colors are different wavelengths of light reflected by the object itself. The colors used in bingata seem to represent the very light that shines on Okinawa.

Despite the great loss from the devastation of war, bingata has survived. Around the reconstructed Shuri-jo Castle, many bingata workshops are located, as if to recreate the Kingdom that has disappeared. Some of the Ryukyu-style bingata outfits from the Kingdom period that miraculously survived by being relocated from the island prior to the war are now owned by both the Okinawa Prefectural Art Museum and the Japan Folk Crafts Museum. The Palace Museum in Beijing also holds a few pieces of bingata sent from the Ryukyu Kingdom during the Qing Dynasty period. They are the examples of bingata made with the highest skills at the time. People had literally put their lives at stake in dyeing these textiles under the name of the Ryukyu Kingdom. Nevertheless, these textiles do not show any sense of despair. Rather, they hold the unparalleled beauty only achievable by putting life at stake. The sunlight from the Kingdom period still shines from the swaying cloth.

- Textile :

- Aizu Momen

- Textile of Okinawa

- Ryukyu Bingata

- Ryukyu Kasuri

- Yuki Tsumugi

- Old textile

- Dyeing :

- Indigo